visitors from space

Several meteorites strike Ireland each year. Join Dr Mike Simms in exploring meteorites in the Ulster Museum collection.

Meteorites are pieces of rock or metal that fall to Earth from Space.

The fall of a meteorite is an extremely rare event. Fewer than twenty separate falls are recovered worldwide each year and the Winchcombe (Gloucestershire) meteorite fall of 28th February 2021 was the first recovered in the UK since 1991.

Most meteorites come from the asteroid belt, a mass of rocky fragments and small battered 'planetesimals' that orbit the sun between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. These asteroids represent the remnants of small planets that formed, and were shattered by collisions, billions of years ago.

Scientists recognise more than 100 distinct types of meteorite from their different chemistry. Most represent a separate planet or asteroid somewhere in the Solar System. For most people a much simpler classification - iron meteorites, stony meteorites, and stony-iron meteorites - will suffice.

Meteorites have huge scientific importance. They provide the only direct evidence we have for the composition of objects in our Solar System beyond our own planet and moon, and of events that happened early in the Solar System’s history.

Iron meteorites: Shattered fragments from a planet’s core

Fewer than 5% of meteorites seen to fall to earth are of iron, but far more iron meteorites have been found because they are so obviously different from rocks on Earth. The largest meteorites found on Earth are made of iron, because iron is tough and withstands the immense stresses of speeding through our atmosphere better than stony meteorites.

The largest meteorite in the museum’s collection, at 113kg, is made of iron with a few percent nickel, and was found in the Gibeon region of Namibia, in southern Africa. Its surface is covered with shallow pits that were sculpted by the superheated air that enveloped it on its descent through our atmosphere.

Crystals from a planet’s core: The Widmanstatten pattern

Iron meteorites represent fragments from the cores of small planets long ago destroyed by collisions. When sliced through and etched with acid some of these iron meteorites show a distinctive crystalline structure in the iron-nickel alloy.

Known as the Widmanstatten Pattern, this formed as the planet’s core cooled very slowly, in some cases at just a few oC per million years.

This example is from the Gibeon region of Namibia, in southern Africa.

Stony meteorites - Bovedy and Sprucefield: Northern Ireland’s last meteorites

Of three meteorite falls recovered in Northern Ireland the most recent was on 25th April 1969. Pieces were found at Bovedy, near Garvagh, and Sprucefield, Lisburn, after a spectacular fireball was seen and a sonic boom heard.

These are a stony meteorite of a type called an Ordinary Chondrite. ‘Ordinary’ because it is the most common type of meteorite to fall to Earth (but still very rare), and ‘Chondrite’ because it is made of small silicate spheres called chondrules. The chondrules, visible as small circular objects in the polished slice, are unusually clear in the Sprucefield meteorite pictured above and have helped scientists to understand how they formed in the early days of the Solar System.

Crumlin: A meteorite whisked away

The Crumlin, County Antrim, meteorite fell on 13th September 1902. It is an Ordinary Chondrite, like the one that fell at Bovedy and Sprucefield, but the chondrules in it are much less distinct. Their outlines have been blurred by the effect of heating of the parent asteroid early in the Solar System’s history.

Within weeks an expert from the British Museum had visited the owner, a Mr Walker of Crosshill, and taken the meteorite back to London. This caused great consternation in Northern Ireland and an amusing cartoon appeared in the local press accusing the British Museum, in the guise of John Bull, of theft.

The Murchison meteorite: Amino Acids from Space!

This meteorite is just one of more than 100kg of meteorites that fell over the town of Murchison, in Victoria, Australia, on 28th September 1969.

It is a rare and fragile type of meteorite called a Carbonaceous Chondrite, characterised by a scattering of small chondrules and the presence of various carbon compounds. Among these are many different amino acids – chemicals that are the building blocks of life! Carbonaceous Chondrites like this probably formed in the outer part of the Solar System, beyond the orbit of Jupiter, and they show evidence that they once contained water ice.

A Mexican meteorite and the oldest objects in the Solar System

On 8th February 1969 more than two tons of a rare type of meteorite, a Carbonaceous Chondrite, fell near the town of Allende, in Mexico. It has since become the most studied of all meteorites.

Among the abundant spherical chondrules of which it is made are small irregular objects called Calcium Aluminium Inclusions (CAIs). They were the first solid objects to condense from the hot gas and dust cloud right at the beginning of the Solar System. Radiometric dating (using the decay of radioactive elements within the CAIs) shows that they formed 4567 million years ago. Scientists consider this to represent the age of our Solar System.

But the CAIs are not the oldest objects within the Allende meteorite. It also contains many microscopic grains of minerals such as graphite, silicon carbide and even diamond. Analysis of these shows that they come from stars other than our own Sun and so they must be older than the Solar System. Some may be as much as 7 billion years old!

Our Allende meteorite shows clearly the dark outer fusion crust, created by intense heat as it descended through our atmosphere, the circular outlines of chondrules on the cut surface, and an irregular pink and white CAI on the broken surface. This CAI is the very oldest object on display anywhere in the Ulster Museum!

The Millbillillie meteorite: a piece of the dwarf planet Vesta

Some stony meteorites are called achondrites because they do not contain the spherical stony pellets (chondrules) that characterise chondrite meteorites. Instead, they are made of crystals and represent solidified magma from the crust of a planet.

Studies have shown that some of these achondrite meteorites, including this example, actually come from the dwarf planet Vesta. At almost 600 km across, Vesta is the second largest of the asteroids in our Asteroid Belt.

This is just one of a shower of meteorites that fell near the cattle station of Millbillillie, in Western Australia, in October 1960. The glossy fusion crust was created by the intense heat as it descended through Earth’s atmosphere.

A meteorite from the Moon

More than 380 kg of Moon rock were brought back to Earth by the Apollo astronauts, but at least as much has been found on Earth in the form of Lunar meteorites. These are rocks that have been blasted from the Moon’s surface by the impact of a large meteorite, and some of these fragments have eventually fallen to Earth as meteorites themselves.

No lunar meteorite has ever been seen to fall; all have been found, much later, in the dry deserts of Africa and the blue icefields of Antarctica. But we can be certain that they are meteorites from the Moon because we can compare them with the Apollo Moon samples.

The Moon rock in this small specimen was melted by the energy of the impact that launched it from the Moon, which is why it is such a dark colour. It was found in Oman in 2001.

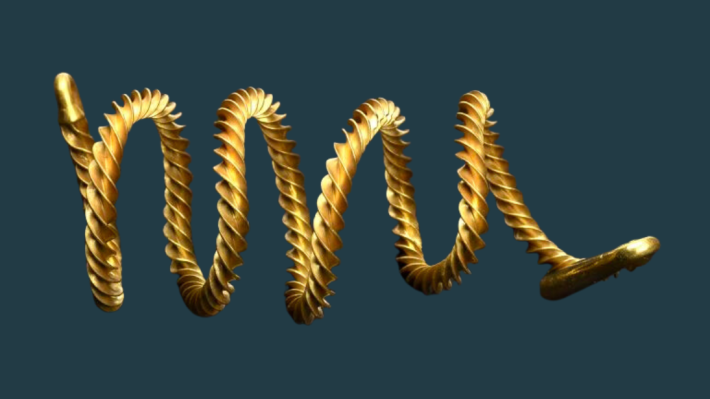

Stony-iron meteorites: Seymchan pallasite

Pallasite meteorites are a type of stony-iron meteorite containing fragments of olivine, a green silicate mineral, embedded in iron-nickel metal. The iron came from a planet’s core while the olivine was from the Mantle, the stony layer that surrounds a planet’s core.

Olivine melts at a much higher temperature than the iron and, since the two materials are like oil and water, they don’t readily mix. It is thought that collision with another small planet caused molten iron-nickel from the core to be injected into solid olivine of the mantle above to create what we see in pallasite meteorites.

This is a slice through a piece of a large meteorite that was discovered in a stream bed near the town of Seymchan, in the Magadan region of Siberia. The iron has been etched to show the crystalline structure.

You May Also Like

The Best of Health

A few key elements are vital for life. Quite a few more are needed in tiny amounts to ensure our continuing good health. But there are others that we really don’t want to find in our diet...

The Prehistoric World of Neave Parker

Neave Parker was an artist who made reconstructing the likenesses of dinosaurs and other extinct animals his speciality.

How did they do that?

One of the fascinating aspects of the past is pondering on how things were made without the aid of modern technology. Learn more about these intricate objects from our experts.